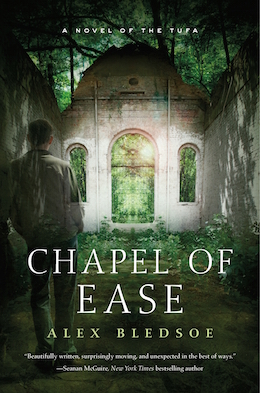

When Matt Johanssen, a young New York actor, auditions for “Chapel of Ease,” an off-Broadway musical, he is instantly charmed by Ray Parrish, the show’s writer and composer. They soon become friends; Matt learns that Ray’s people call themselves the Tufa and that the musical is based on the history of his isolated home town. But there is one question in the show’s script that Ray refuses to answer: what is buried in the ruins of the chapel of ease?

As opening night approaches, strange things begin to happen. A dreadlocked girl follows Ray and spies on him. At the press preview, a strange Tufa woman warns him to stop the show. Then, as the rave reviews arrive, Ray dies in his sleep. Matt and the cast are distraught, but there’s no question of shutting down: the run quickly sells out. They postpone opening night for a week and Matt volunteers to take Ray’s ashes back to Needsville. He also hopes, while he’s there, to find out more of the real story behind the play and discover the secret that Ray took to his grave.

Matt’s journey into the haunting Appalachian mountains of Cloud County sets him on a dangerous path, where some secrets deserve to stay buried…

Chapel of Ease, the fourth novel in Alex Bledsoe’s Tufa series, is available September 6th from Tor Books!

1

No matter how fast I ran, or how many times I zigged and zagged, I heard the dog getting closer. First his paws, then his growling, then his breathing.

Finally, I gave up. I stopped, groped around until I found a fallen branch, and backed up against the biggest tree I could find. I held the stick like a baseball bat and waited to see my pursuer.

He—I assume it was a he—padded out of the shadows into a thin patch of moonlight. In my terrified state he looked as big as a horse, and the first thing I thought of was The Hound of the Baskervilles. Reading that story as a child, I always wondered how anyone could be so scared of a mere dog. Now I knew.

He had short hair that shone where the moonlight hit it and rippled over his muscles. I couldn’t see any teeth when he growled, but I was pretty sure they’d be huge, too. The stick in my hand could not have felt more inadequate. I remembered Rick Moranis in Ghostbusters, facing down a hellhound, and thought, Who ya gonna call? Nobody came to mind.

He was less than ten feet away now, and his masters drew close as well, although with far less speed and grace. Apparently they trusted the dog to do most of the dirty work of catching me. Which, of course, he had.

And now he was about to finish the job.

Then, for no obvious reason, he took a step backwards and growled in a completely new way. Suddenly he was frightened.

Something moved in the corner of my eye. Had the Du-rants flanked me, or had I just run straight into their clutches? I turned.

A man emerged from the forest and stood beside the same tree I cowered against.

Although I couldn’t see his face, his body shape told me it wasn’t C.C., or his friend Doyle. All the Durants I’d seen had been larger as well. He was shorter, and slighter, than any of them. He had an unruly shock of dark hair silhouetted by the moonlight, and wore overalls. He carried no weapon, yet the dog continued to back away, his growl now becoming a low, keening whine.

I glanced from the dog to the man, not sure what exactly was happening. Why did this guy frighten the dog so much?

And then I saw the obvious. I mean that literally: faintly but distinctly, I saw the moonlit trees through the man’s form. He was a ghost.

A haint.

I suppose, though, this needs some background.

* * *

“His name’s Ray Parrish,” Emily Valance said over her cup, her pink bangs falling to her Asian eyes. We sat at one of the tables in the tiny Podunk Tea Room on East Fifth Street between Second and Bowery, sipping tea that cost more than some meals I’d had back in my hometown. Neither of us were natives—I was from Oneonta, and Emily was from California—but we both felt like we belonged nowhere else than this city.

“Ray Parrish,” I repeated. “No, I don’t know him.”

“No reason you would. He hasn’t had anything produced yet. Well, unless you count a one-man show he did, Dick from Hicksville.”

“Dick from Hicksville?” I repeated rather archly.

“I know how it sounds, it’s a terrible title. But it was great. It was all about the difficulties he’d had in making a dent in the theater scene. And, oh my God, was it funny.”

“So it was good?”

“It was brilliant. I couldn’t stop humming one of the songs for two weeks.”

That got my attention. Whenever a professional theater person got an earworm from a new song instead of a Broadway classic, it meant the new piece really was pretty good. And even though Emily was a terrible dancer, she knew good music. “And what’s this new show about, then?” I asked.

“He’s being all hush-hush about it. I know it’s got something to do with mountain people. You know, like from down South?”

“What, like Li’ l Abner?”

“I seriously doubt that. He’s from there, so I don’t think he’d be making fun of it. And he let me hear the big ballad he’s written for the female lead.” She paused for effect; actors know just how to do that. “And I want to be the one to sing it, Matt. I do. It’s a career-maker, and I’m not just saying that. If the rest of the score is as good as what I’ve heard, it can’t miss. It’s like it reaches inside you and brings up all these emotions you haven’t felt since you were a teenager, except it’s not like a kid would feel it, you know?”

I shook my head. “Emily, I have no idea what you’re trying to tell me.”

She laughed at her own words. “Good God, I do sound insane, don’t I? It’s so hard to describe it, you just have to hear it. You just have to.”

I sipped my own tea. I’d known Emily for a couple of years now, and enthusiasm wasn’t something she came by naturally. She was a great singer, an okay actress, and a lousy dancer, all facts she knew very well. But she had nursed a mental image of herself in a Broadway musical since girlhood, and she wasn’t about to let a minor detail like lack of appropriate talent stand in her way. Others found her overbearing and bitchy, but I actually admired her. And anything that had a single-minded performer like her this fired up was something I probably needed to pay attention to.

“So when are the auditions?” I asked.

She shook her head. “No auditions. He’s just calling up people he knows and asking them to come to a rehearsal studio. If he can get along with them, they’re in.”

“He’s personally doing it? Is he directing it?”

“No. Neil Callow is.”

“Neil Callow? No shit?”

“No shit. He’s apparently been quietly in on this from the beginning. I heard Ray even slept on his couch for a couple of months when he couldn’t afford his own place.”

Neil Callow had done some huge shows; in fact, I’d danced in one of them, Sly Mongoose, three years ago. He was a mercurial guy, to be sure, but his talent was undeniable, and anyone who’d worked for him once would jump at the chance to do it again.

“You keep calling him ‘Ray,’ like you know him,” I pointed out.

“I… might,” she said, and looked away for a moment.

“‘Might’ as in ‘might have been out with him’?”

“Maybe.”

“‘Maybe’ as in ‘more than once’?”

She nodded sheepishly. “But, Matt, he’s so old-fashioned and nice, you know? Like I always imagined a real Southern gentleman would be.”

“So you can’t bring yourself to fuck him just to get a part?”

She stuck out her tongue. “No. I don’t do that anyway, you slut.”

I knew she didn’t, but it was still fun to tease her. “So has he called you? In a professional sense?”

“No,” she said, unable to disguise her bitterness. “He hasn’t. And I can’t ask about it. Mainly because if he said, ‘because you’re Asian,’ then I’d have to punch him in the face.”

I nodded. Theater wasn’t as bad as Hollywood at race-blind casting, but it was still hard sometimes for actors of an undeniable race to get roles in shows where the characters weren’t race-specific.

“Well… there’s still time, right? They haven’t started rehearsing.”

“I suppose.” She peered into her cup. A guy looked her over blatantly as he left and said, “I sure could do with some Chinese takeout.” She ignored it. After a moment she said, “I have to sing those songs, Matt. I don’t know how to describe it to you, but it’s like he was writing them for me. I know, I know, every singer wants to think that, and he wrote most of these long before I met him. It’s just… they’re me. They’re my hopes and dreams and nightmares.” When she looked up, there were tears in her eyes. “If I don’t get that call, I don’t know what I’ll do. I really don’t.”

At that moment my own phone rang. The number didn’t come up as one I recognized, and I was about to let it go to voice mail, when Emily said, “Go ahead and answer it, I need to freshen up.” She scurried to the restroom before anyone else in the place saw her crying.

I answered. “Hello?”

“Is this-here Matt Johansson?” the voice on the other end said in a distinctive and heavy Southern drawl.

“It is.”

“This is Ray Parrish. I don’t reckon you know me, but I saw you in Regency Way and thought you were great.”

My heart pounded, and I quickly went outside. I glanced at the restroom door through the front window and willed it to stay shut. “Thank you. What can I do for you?”

“Well, I’ve got a new show that I’ve written, and I’d like to talk to you about playing one of the leads. I think you’d be terrific, and really, I just want to see if you, me, and the director get along.”

“Who’s the director?” I asked as casually as I could.

“Neil Callow.”

Oh my God, oh my God, oh my God! my brain screamed at this confirmation. This is really happening, right here, right now. My voice said, “Oh, I’ve worked with Neil before. Sounds interesting.”

“All right. I’ll text you the address and the time. Great talk.ing to you.”

“Great talking to you, too,” I said, hoping I didn’t sound as numb as I felt. That could come across as blasé, and I was anything but that.

The call ended, and Emily emerged from the tearoom. “What’s wrong?”

“Wrong? Nothing. Why?”

“You look like you’ve seen a ghost. Who was on the phone? Did you get bad news?”

“That? No. It was…” Her concern was so genuine, and I’m such a terrible liar, that my brain refused to cough up a reasonable deception. “Some scam call trying to tell me I had a bunch of money coming because some rich uncle died. Heh-heh.”

Emily stared at me. I couldn’t blame her. I felt myself turn red.

“They called you,” she said at last. It was a whisper, but the jealousy and accusation in it were so loud, I was sure they heard it in Queens.

I lowered my head and nodded. “Yes. I’m sorry. I danced in one of Neil’s shows, so they thought…” I wasn’t about to tell her they’d offered me one of the leads.

Fresh tears filled her recently re-mascaraed eyes. Without another word she ran off down the street. I knew better than to follow; the last thing she wanted right now was my presence reminding her that she’d been passed over yet again. I wondered if she’d mention this to Ray, or if this spelled the end of that relationship. Or perhaps her friendship with me.

I went back inside, drank the rest of my tea, and Emily’s, in a kind of blank daze. It was just another Off-Off-Broadway show, an original musical at that. The run would probably be two weeks at the most, and the money barely enough to exist on. But I felt a surge of excitement building in me far out of proportion to the reality. Was this how those first performers in A Chorus Line or Rent felt just before going in to audition for those shows? Did they, at some subconscious, instinctive, primal level, just know? Because looking back, it was clear I did.

I stayed in that daze as I headed home to Bushwick. Ray hadn’t described it as an audition, and Emily said they were just calling people they already knew could perform. But I didn’t want to be caught off guard. I mentally ran through a list of songs I knew I sang really well, and then tried to remember if I had sheet music for them. If not, at least I had time to download it.

And while I was downloading, I could find out a little more about Ray Parrish.

I knew nothing about this show yet, I kept reminding myself. But I already knew I wanted it.

2

The entrance to the rehearsal studio where I was supposed to meet Ray Parrish and Neil Callow was at the top of a steep narrow staircase that ran along the outside of the building, ending at a covered stairwell. The lightbulb was out, so as you looked up the stairs, it was easy to imagine going into that blackness and never coming out.

I checked the address again. Yep, this was it, above a fortune-teller’s storefront that advertised, in neon, Psychic Crystal and Tarot Readings. Perhaps I should stop in with Star Aurora and see if she had any insight. Then I saw that “tarot” was misspelled Torot, and decided that was a sign.

In college, we’d studied old hero myths and I seemed to recall something about the hero having to pass through the underworld at some point. It was ironic that the underworld might be located at the top of the stairs, but as I slowly took the steps, it certainly felt like I was embarking on something epic.

It hadn’t taken long to learn all the Internet had to tell about Ray Parrish. He was from a small town in Tennessee, and he’d come to New York as a session musician, working with some of the biggest names in the business. But he always wrote his own songs, too, and after discovering the fringe theater scene, he decided to put his energies toward writing for the stage. At first he worked with established writers, putting songs to their stories, but now he was ready to do it all himself.

I found only two pictures of him: one was a rehearsal shot, and he was far in the background, while the other was an actor’s backstage photo posted on Facebook. In it, Ray sat at an upright piano, hunched over the keys with the kind of serious intent I’d seen on classical performers. Yet he wore a baseball cap with the silhouette of a tractor on it. Ray himself had no social media presence, and I wondered just how weird he was likely to be.

Fortunately, in real life Ray Parrish had a grin that lit up the room. When I tentatively opened the door to the studio, Ray sat in a folding chair beside the piano, engrossed in texting someone. He turned suddenly, and smiled. “Matt Johansson!” he said, and jumped to his feet.

He approached me with his hand out. “I’m really glad you could make it, Matt. I’ve been telling Neil here all about you. I saw you in Regency Way, and you were phenomenal. That song at the end, where you had to break down… you had the audience riveted.”

“Having a good song helped,” I said.

“I reckon so. But I saw it three times, and once with your understudy, so I know how much of it was just you.”

“Thank you.” Wow, I thought. I’d missed one afternoon show after the train broke down and stranded me, and my understudy had gone on in my place. By all accounts he’d done fine, but I was lucky that hadn’t been the only show Ray saw.

“Neil!” Ray called. “Come meet Matt Johansson.”

Neil Callow strode over to us. He was short, bulky, and wore his hair the same way he must have in the ’90s. “Yes, no matter how many times I tell him that I know you, he just can’t seem to retain it. Good to see you again, Matt. Are you still dating Chance Burwell?”

Chance had been a featured dancer in Sly Mongoose, and we’d been a couple for a few months. It hadn’t worked out, but the parting had been genial. “No, he and I broke up.”

“That’s too bad. I heard he was working on a cruise ship.”

“We haven’t kept in touch.”

“Well, that’s all in the past. Let’s get started on the future. Take a seat.”

Even though I’d been told this wasn’t an audition, it was hard not to think of it that way. That was okay, though; audi.tions were nerve-racking for some, but I always found them exciting. Even when I didn’t get the part, which was most of the time, I tried to always leave a good impression, since you never knew what might happen someday. My presence here right now was a perfect sign of that.

“I think we have a mutual friend,” I said to Ray. “Emily Valance.”

He smiled, and I swear he blushed a little, too. “Oh yeah, I know Emily. She’s amazing.”

“She says very nice things about you.”

“Really? Like what?”

“You can talk about that in study hall, boys,” Neil teased good-naturedly. “Right now, Ray, why don’t you tell Matt about the show?”

“Sure!” Ray said, brimming with excitement. “It’s set back in my home place, Needsville, Tennessee. Ever heard of it?”

I shook my head.

“Well, it’s little-bitty, so I’m not surprised. It’s way up in the Appalachian Mountains.” He pronounced it Apple-Atcha, not Apple-LAYcha, the way I’d always heard it. “It’s about a place called a chapel of ease. Know what that is?”

Again I shook my head, but volunteered, “A whorehouse?”

He laughed. “Naw, but that might make a good story, too. No, it’s like a branch church; when the real church is too far away for a lot of people to get to, they set up a small one to kind of fill in the gaps. The preacher comes around every so often to do weddings, baptisms, and so forth. It gives the distant faithful a place to gather.”

I had not been raised in any religion; in fact, I’d only set foot in churches for weddings and funerals. So this was as foreign to me as the Russian peasantry in Fiddler on the Roof. “Okay,” I said. “Sounds interesting.”

“It’s about two trios of characters, one from the Civil War, one modern. In both, two of the people are in love and about to get married, and the third one is secretly in love with one of the others. So it’ll have ghosts, and murder, and all the things that make theater great.” He grinned with unabashed delight. “The thing that pulls the two stories together is the mystery of what’s buried in the floor of the ruined old chapel.”

“Which is?” I asked.

Ray grinned in a way I would soon hear him characterize as “like a possum.” “I can’t tell you that. See, in the show, we never find out.”

“Really?”

“Really,” Neil said with a weariness that implied he and Ray had discussed this issue a lot. “I know how it sounds, but in the context of the show, it really does work.”

“But do you know?” I asked Ray.

“Yeah, of course I know.”

“You should also tell him,” Neil said more calmly, “that this is based on a true story.”

“It is,” Ray agreed. “It’s something I grew up hearing about, and I used to sneak over to the old chapel just because they told me I couldn’t. I always knew someday I’d use it as the basis for something, so I kept turning it over in my mind until I came up with this show.” He did a drumroll with his hands on the table. “So you want to try some singing? We’ll do some.thing you already know to warm up, then we’ll try some stuff from the show.”

“Ray’s not just the writer and composer,” Neil said. “He’s also the musical director.”

“And I intend to be playing piano in the orchestra, too. Well, it’ll be more of a band. But I want to be there.”

While Neil went to sit by the wall so he could watch and listen objectively, I followed Ray to the piano. I couldn’t help myself checking him out: he was lean, lanky, and walked with his head hunched down the way some tall guys do. His long jet-black hair was tied back in a loose ponytail, as if he’d done it just to get the hair out of his way. He had high cheekbones, and at the time, I thought he must have some Native American in him.

He settled down at the piano bench and I handed him the music of one of my favorite songs, which also happened to to.tally show off my voice: “Synchronicity II,” by the Police. He looked at it, smiled knowingly, and said, “Oh, man, I love this one.” Then he imitated Sting’s voice: “Dark Scottish loch.” He hit a note for me, then said, “Ready?””

I tore through the song, which he played slightly faster than I was used to. He added little fills and at one point during the cacophonous guitar solo part, hit the keys with his elbows. We both laughed. He finished with a glissando.

Because we went so fast, I didn’t have time to worry and second-guess myself, but just plowed ahead with as much full-throated enthusiasm as I could muster. I almost wished I had a microphone on a stand in front of me, to grab and use as a prop.

Neil politely applauded when we finished. He’d done this long enough to expertly hide any response other than basic appreciation for effort. “Matt, I can’t remember: Can you sight-read?”

I nodded. Ray flipped through some music and said, “Here, let’s try this one.”

The song he handed me was called “A Sad Song for a Lonely Place.” I read through it quickly, getting a sense of the rhythm. It was comfortably in my range. “Okay,” I said.

“I’ll go through it once, and then you can come in,” he said, and began to play.

Except that “play” doesn’t do it justice. I knew he could play from our first number. And I knew a lot of great musicians, especially pianists, but I’d never seen or heard anyone like him. His fingers worked the keys with the fluidity of a mountain stream, and his body rocked with the grace of a willow bending in the wind. And the music itself was so touching, so affecting that I totally missed my cue. He looked up at me with

a grin and, still playing, said, “Wait till I come around again.”

I did, and then at his nod, I began:

The stones were set to last forever

But the mortar crumbles away

The trees may stand for centuries

But eventually fall to decay

And me, I’m a blink of the great oak’s eye

My time so pitiful and short

So why does this pain cut me so to the quick

And leave a hole in my chest for my heart?

I sang as simply and directly as I could. I understood the audition process: this part wasn’t about anything other than making sure I could hit the required notes with as little effort as possible. And I could. It was like it was written for me.

That made me think back on Emily, who’d felt so certain when she heard the songs from this show that they were meant

for her. I wondered how many other actors were wandering around New York thinking the same thing.

When we finished, Ray glanced back at Neil, who nodded very slightly.

“That was great, Matt,” the director said. “But I wonder if you could try it a little differently? Emphasize the weariness. Try to bring out the weight of time that the singer is feeling. Does that make sense?”

“You bet.” Neil was seeing if he and I really understood each other, and if I could take direction. So I sang it again, the way he requested, and damn if the song wasn’t even easier this way. My first attempt missed a crucial element, and now I’d found it.

When I finished, I wasn’t even out of breath. If anything, the song had energized me.

Ray flipped through the sheets on the piano’s music stand. “Let’s try another one,” he said eagerly. “Your character doesn’t sing all these, naturally, but I’ve heard myself sing ’em so much, it’s just a treat to hear a different voice. Okay with you, Neil?”

Neil mock-shrugged. “Sure. But just so you know, Matt, it’s not going to be a one-man show.”

I laughed, and Ray turned eagerly to me. “You up for it?”

“You bet,” I said. I tried not to get excited and read any sub.text into his “your character” comment. I knew from experi.ence that I didn’t actually have the role until my agent got that all-important offer from the producers. But if the rest of the songs were as beautiful as the one we’d just done, then I wanted to sing them just for the pleasure of it.

And they were.

The next song was clearly meant for a woman, and was al.most out of my range. Was this one running around Emily’s head even as I sang?

Too many sorrows

Too many lies

Too many failures

Too few tries

His love left me hopeless

His touch left me cold

And I, I run to him

Whenever he calls.

We sang the whole score. A few of the other songs intended for female characters really strained my voice, but I never cracked and we all laughed when I couldn’t quite hit the high notes. The story that emerged from the score was simple yet moving, a symphony of emotion rather than plot. If it could be effectively translated to the stage, it would be incredible, of that I was absolutely sure.

When we finished the last song, Neil said, “That was great, Matt. Except for that one high note,” he teased.

“I think I have the wrong anatomy for that one.”

Ray stood, shook my hand, then impulsively hugged me. “Thank you, Matt. Sorry for taking up so much of your time. This was supposed to be a quick meet and greet.”

He glanced at Neil. If they had a predetermined signal, I didn’t catch it. “We’ll be in touch,” Neil said.

Ah, the old “we’ll be in touch” line. Well, it had been a fun couple of hours. “Thanks.”

“I know what you’re thinking,” Neil said as he walked me to the door. “But we will be in touch. This was extraordinary.”

I still didn’t get my hopes up. “Thank you, Neil. Great to see you again. Ray, nice to meet you.”

Ray looked up from straightening his sheet music. “Hey, you got any plans for right now?”

That caught me off guard. “Well… no.”

“I’m starving. If I don’t eat, I get cranky. Want to go grab a sandwich?”

“Uh… sure.”

I looked at Neil, wondering if he’d invite himself along, wishing like hell that he wouldn’t. He shook his head. “I have at least one agent to call,” he said with a knowing little smile. He handed Ray some money. “Can you bring me back a pastrami on wheat?”

“Sure.” Ray put his hand on my shoulder. “Come on.”

We left the theater and walked three blocks down to Yancy’s, a sandwich shop I’d never been to. It smelled great, though, and it wasn’t crowded. We ordered at the counter and waited for our sandwiches at a table in the front window.

I watched Ray for any clues that this was meant as a date. Sure, he’d dated Emily, but this was New York, and lines were so blurry here that you had to be in New Jersey to see them, and then only if you squinted. I didn’t know what their couple status was, or even if they had one. But I did know that it prob.ably wasn’t a good idea to get into even a flirting relationship with the composer of the show my agent might, at this very moment, be making the deal for. Yet he was so cute, in an irresistible floppy-dog sort of way. I wanted to fix his ponytail and turn down his askew collar, using it as an excuse to touch him.

He straightened (no pun intended) me out right away. “Just to be clear, man, I’m not gay, so I’m not hitting on you. I was just really, really impressed with your singing. You have the voice I’ve always heard in my head for Colton.”

“Wow, thanks,” I said, and swallowed my disappointment. This was work, after all.

“Neil better be signing you up right now. You mind dyeing your hair black like mine?”

“No. So Colton is based on you?”

“No, not at all. But all the Tufa have the same black hair.”

“What’s a ‘Tufa’? Is that your tribe?”

He laughed. “Yeah, sort of. We’re not Indians, though. We’re—”

The server arrived with our sandwiches, and since the shop’s delicious smell had made me just as ravenous, we tore into

them before he could tell me more. When we came up for air, I said, “You were telling me about your people?”

“Oh yeah. Well, according to legend, the Tufa were already in Appalachia before the ancestors of the Native Americans

came over from Asia. Nobody knows where we came from, or what race we descended from. And with this hair and skin”—his skin was a dusky olive, like a swarthy Mediterranean—“a lot of people thought we were part black, which you definitely didn’t want to be in Tennessee back in the day. So we just kept to ourselves up in the mountains, and still pretty much do.”

I’d never heard of them before. “Interesting.”

“So most of the characters in the story will have this same black hair.” He grabbed a stray strand and held it out as an

example.

I briefly wondered if that would make it hard to tell us apart onstage, but then remembered that would be Neil’s problem,

not mine. And only if I got the job.

“So I gotta ask,” he inquired between sloppy bites. “What did you think of the songs?”

“They were great. Seriously.”

“I’ve been working on them a long time. A really long time,” he added with personal irony that I didn’t get.

“So was Neil serious? That this was a true story?”

He wiped his chin as he thought. “Some parts are true, some are made up. The stuff set in the Civil War is all true, or at least it was told to me as true. But there are rules about… Well, a lot of the Tufa back home don’t believe any of us should ever do anything to draw attention to ourselves. Sure shouldn’t tell our own stories out of school, if you know that expression.”

I didn’t, but the context made it clear. “Will you get in trouble?”

“Naw. It’s not like anyone in Needsville follows the New York theater scene. Besides, the songs are all mine, and ultimately so is the story. Ain’t nobody’s business who I tell it to, right?”

“Right,” I agreed, wishing his Southern accent wasn’t so damn hot.

* * *

When I got home, I got online and looked up the people he’d mentioned. At first I tried spelling the word in overly complicated ways: “Toupha,” “Tewpha,” and so forth. It wasn’t until I tried the simple T-U-F-A that I got a ton of relevant hits.

Well, as “relevant” as this sort of thing could be. At the time, I was more amused than anything else. As he said, they weren’t a Native American tribe. They also weren’t Scotch-Irish, like most of the other original white settlers of Appalachia. If you believed the Web sites, the Tufa did predate both of those.

But the anthropological mystery paled beside the paranormal ones. Supposedly the Tufa had secret magical powers, could seduce anyone, and used their musical skills to get their way. They lived in a tiny, isolated community and had very little to do with the outside world, even today. Their most notable citizen was Bronwyn Hyatt, a soldier who’d been captured and then rescued on live TV during the Iraq War.

I poured a glass of wine and settled in to read these stories in detail. After all, if I got the part, I’d be tasked with bringing a member of this subculture to life. I glanced in the mirror and wondered what I’d look like with black hair; my own was light brown, almost blond if I spent any time in the sun.

As the wine took hold, I realized two important things: I really wanted to sing those songs again, for an audience. It had very little to do with being the star, or even being onstage. I just wanted to share them with other people, to watch them have the same effect on strangers that they had on me. They were that good, and that original.

And second… I had a totally hopeless crush on Ray Parrish.

Excerpted from Chapel of Ease © Alex Bledsoe, 2016